We all know that apps collect our data. Yet, one of the few ways to discover what an app does with our information involves reading a privacy policy. Let’s be honest: Nobody does that. So late last year, Apple introduced a new requirement for all software developers that publish apps through its App Store. Apps must now include so-called privacy labels, which list the types of data collected in an easily scannable format. The labels resemble a nutrition marker on food packaging. These labels, which began appearing in the App Store in December, are the latest attempt by tech designers to make data security and digital privacy, which are linked, more accessible for all of us to understand. You might be familiar with earlier iterations, like the padlock symbol in a web browser. A locked padlock tells us that a website is more secure, while an unlocked one suggests a website can be more susceptible to attack.

The question is whether Apple’s new labels will influence people’s choices. “After they read it or look at it, does it change how they use it or stop them from downloading it?” asked Stephanie Nguyen, a research scientist who has studied user experience design and data privacy. To put the labels to the test, I pored over dozens of apps. Then, I focused on the privacy labels for WhatsApp and Signal, the streaming music apps Spotify and Apple Music, and, for fun, MyQ, the app I use to open my garage door remotely. I learned plenty. The privacy labels showed that apps that appear identical in function could vastly differ in handling our information. I also found that lots of data gathering happens when you least expect it, including inside products you pay for. But while the labels were often illuminating, they sometimes created more confusion.

How to Read Apple’s Privacy Labels

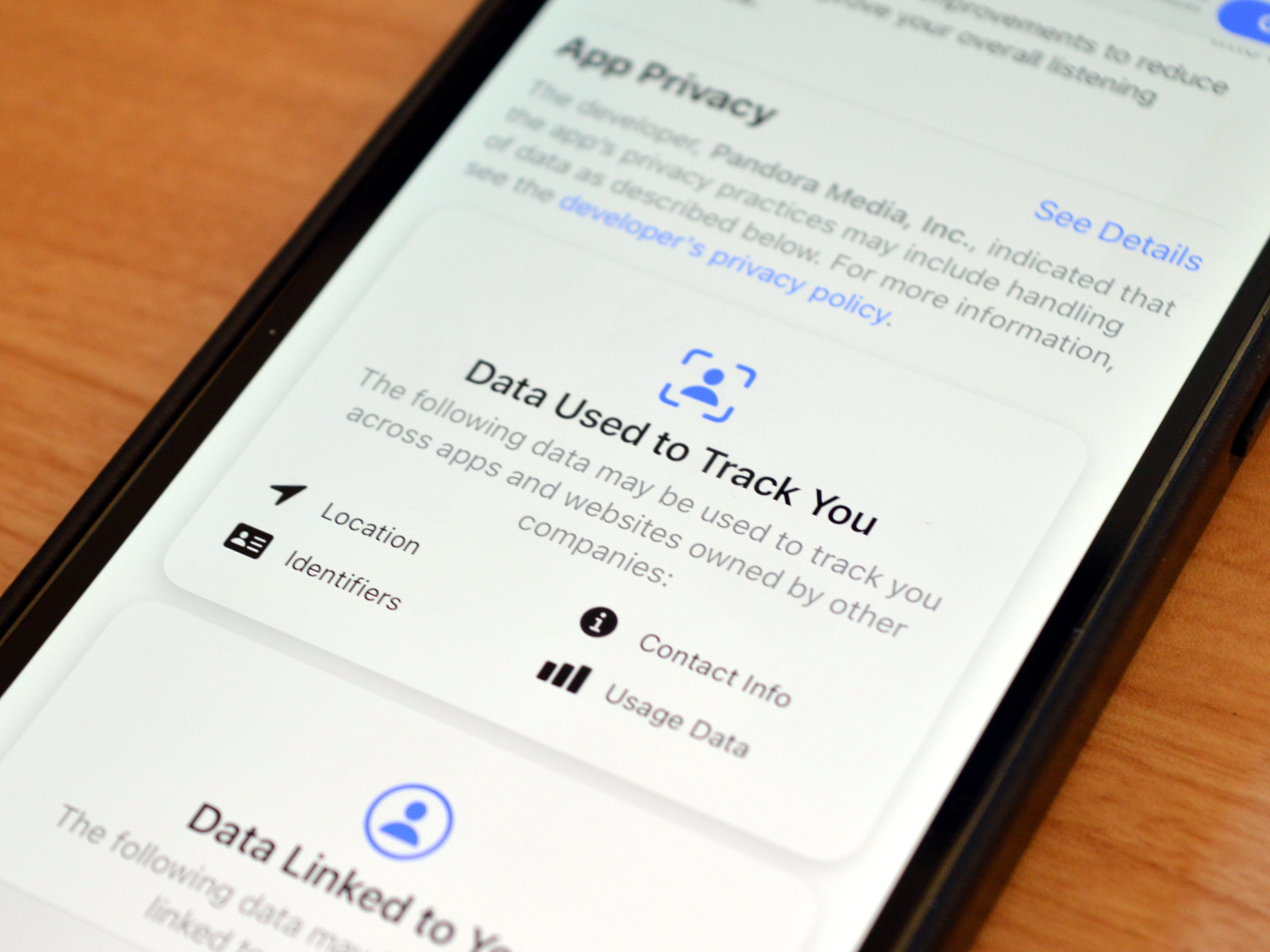

IPhone and iPad users with the latest operating system (iOS and iPadOS 14.3) can open the App Store and search for an app to find the new labels. Inside the app’s description, look for “App Privacy.” That’s where a box appears with the brand. Apple has divided the privacy label into three categories to get a complete picture of the kinds of information that an app collects. They are:

- Data is used to track you. This information is used to follow your activities across apps and websites. For example, your email address can help identify that you were also using another app where you entered the same email address.

- Data linked to you: This information is tied to your identities, such as your purchase history or contact information. A music app can use this data to show that your account bought a particular song.

- Data not linked to you: This information is not directly tied to you or your account. For instance, a mapping app might collect data from motion sensors to provide turn-by-turn directions for everyone. It doesn’t save that information in your account.

Now, let’s see what these labels reveal about specific apps.

WhatsApp vs. Signal

On the surface, WhatsApp, which Facebook owns, appears nearly identical to Signal. Both offer encrypted messaging, which scrambles your messages so only the recipient can decipher them. Both also rely on your phone number to create an account and receive notifications. But their privacy labels immediately reveal how different they are under the hood. The first one below is for WhatsApp. The next one is for Signal: The tags immediately clarified that WhatsApp taps far more of our data than Signal. When I asked the companies about this, Signal said it tried to take less information.

The WhatsApp privacy label showed that the app could access user content, including group chat names and group profile photos for group chats. Signal, which does not do this, said it had designed a complex group chat system that encrypts the contents of a conversation, including the people participating in the chat and their avatars. The WhatsApp privacy label showed that the app could access our contacts list; Signal does not. With WhatsApp, you can upload your address book to the company’s servers to help you find your friends and family using the app. But on Signal, the contacts list is stored on your phone, and the company cannot tap it. “In some instances, it’s more difficult not to collect data,” Moxie Marlinspike, the founder of Signal, said. “We have gone to greater lengths to design and build technology that doesn’t have access.”

Let Us Help You Protect Your Digital Life

A WhatsApp spokeswoman referred to the company’s website explaining its privacy label. The website said WhatsApp could gain access to user content to prevent abuse and bar people who might have violated laws.

When You Least Expect It

I then looked closely at the privacy label for a seemingly innocuous app: MyQ from Chamberlain, a company that sells garage door openers. The MyQ app uses a $40 hub with a Wi-Fi router to open and close your garage door remotely. Here’s what the label says about the data the app collected. Warning: It’s long. Why would a product I paid for to open my garage door track my name, email address, device identifier, and usage data?

The answer: for advertising. Elizabeth Lindemulder, who oversees connected devices for the Chamberlain Group, said the company collected data to target people with ads across the web. Chamberlain also has partnerships with other companies, such as Amazon, and data is shared with partners when people opt to use their services. In this case, the label successfully caused me to stop and think: Yuck. Maybe I’ll switch back to my old garage remote, which has no internet connection.

Spotify vs. Apple Music

Finally, I compared the privacy labels for two streaming music apps: Spotify and Apple Music. This experiment, unfortunately, took me down a rabbit hole of confusion. look at the labels. The first is the one for Spotify. Next is the one for Apple Music. These look different from the other labels featured in this article because they are just previews — Spotify’s label was so long that we could not display the entirety of it. When I dug into the labels, both contained such confusing or misleading terminology that I could not immediately connect the dots on what our data was used for. One jargon in Spotify’s label was that it collected people’s “coarse location” for advertising. What does that mean?

The app pulls device information to get approximate locations to play ads relevant to where those users are. Spotify said this applied to people with free accounts who received ads. But most people are unlikely to comprehend this from reading the label. Apple Music’s privacy label suggested that it linked data to you for advertising purposes — even though the app doesn’t show or play ads. Only on Apple’s website did I find out that Apple Music looks at what you listen to, so it can provide information about upcoming releases and new artists who are relevant to your interests.

The privacy labels are incredibly confusing when it comes to Apple’s apps. That’s because while some Apple apps appeared in the App Store with private labels, others did not. Apple said only some of its apps — like FaceTime, Mail, and Apple Maps — could be deleted and downloaded again in the App Store, so those can be found there with private labels. But its Phone and Messages apps cannot be deleted from devices and do not have privacy labels in the App Store. Instead, the privacy labels for those apps are in hard-to-find support documents.

The result is that the data practices of Apple’s apps are less upfront. If Apple wants to lead the privacy conversation, it can set a better example by making language clearer and less self-serving in its labeling program. When I asked why all apps shouldn’t be held to the same standards, Apple did not address the issue further. Ms. Nguyen, the researcher, said a lot had to happen for the privacy labels to succeed. Other than behavioral change, she said, companies have to be honest about describing their data collection. Most importantly, people have to be able to understand the information. “I can’t imagine my mother would ever stop to look at a label and say, ‘Let me look at the data linked to me and the data not linked to me,'” she said. “What does that even mean?”

Leave a Reply